One family’s journey over generations and continents reflects both the dominant social forces of the times and the powers of fortitude, courage, and the spirit to never give up.

By Afrin Naz, Ph.D., SWE

I am a brown Muslim woman from southeastern Asia who became an associate professor at the Nelson College of Engineering at West Virginia University. Thus, you could say I am a minority in four different ways: race, religion, gender, and ethnicity. For the next couple of minutes, I’d like to take you, the reader, across an odyssey of a hundred years. An odyssey that three other generations of women trekked so I could become the person I am today.

The family framework

In the early 1920s, my 29-year-old great-grandfather married my great-grandmother, a 7-year-old girl from the mountains of Afghanistan. She never went to school, never saw her parents again, and saw her brother visit only twice in her life. Her name was Jamila Begum.

Jamila and my great-grandfather had five daughters and one son. Their third daughter, Amina Begum, was my grandmother. She was 14 years old when she was married to my grandfather Afsar. He was 28. Unlike my great-grandmother, she was literate in Bangla and could even understand English! As a child, I remember her watching some of her favorite American TV shows. Unlike any other woman around her, she was audacious. Amina and my grandfather had seven daughters; the second daughter, Razia Begum, is my mother.

A common Eastern custom was (or still is) that every couple must have at least one son. My great-grandmother Jamila had to go through five pregnancies just to have a boy. My grandma Amina went through seven miserable ones. Finally, she gave up and convinced her husband to raise one of their daughters as a son.

This was in the late 1930s in what is now Bangladesh. At the time, Muslim girls usually did not go to school and were married before turning 15. While this was the case for my aunts, my grandma fought against social norms to send my mother to a convent school for girls.

With my grandma’s full support and her own ambition, my mom became a trailblazer. The first woman in the family to complete high school, she also went past her father and the other men in her family. Eventually, she went to Birmingham University in England, as a Commonwealth Scholar, to pursue her Ph.D. in chemistry.

During her stay at Birmingham University, my conservative grandparents refused to let her stay in university housing. And when looking for an apartment, no landlord would allow her to stay, claiming her “long hair” would clog the plumbing, obviously an excuse to not house a brown girl. My eventual father, a 38-year-old man from India, completed his Ph.D. from the university, began working in London, and gave her his apartment in Birmingham to stay in while she completed her studies. They would marry a couple of years later, in 1965, and settle back in Dhaka, Bangladesh (it was East Pakistan at that time). Sadly, my dad passed away only 13 years later. While my mom never finished her Ph.D. in Birmingham, she remained committed to education for minorities and became the president of Bangladesh’s largest women-only university with 35,000 students.

I am my late mother’s youngest child, with one older brother. I completed my master’s in microbiology at Dhaka University. Later, I married and immigrated to the United States, where I pursued a second master’s, and finally, a Ph.D. in computer science. I want to continue the work of my mother and grandmother and continue making education more accessible for all minorities.

From perseverance came seeds of hope

Asked whether I can identify a common thread among the women in my family, I considered which qualities might have been passed down. Yes, I can see a specific attribute, “never giving up.” The more I am opposed by a situation, the more adamant I become and push harder. I observed the same tendency in my mom and my grandma.

I never met Jamila, my great-grandmother, but I can see her life in my mind’s eye. Can you imagine? A girl who was taken away from her parents, whom she would never see again, brought to a new country with unknown culture and language, all at the age of 7. Other than perseverance, did she have any chance of survival?

As a girl, I accompanied my grandma on visits to her childhood home, where Jamila had raised her. Located in downtown Dhaka, a densely populated city, it was like most old Muslim houses, with two separate sections. The section called “Andar-mahal,” which means inner house, included the bedrooms, dining area, and kitchen. No outside men were allowed there, and to leave the home women were required to wear a hijab and a burqa (additional outfits covering their whole body). Without wearing these coverings, the only outdoor place allowed was the roof, which was surrounded by wall 10 feet tall, with some holes for the women to see the outside world.

After her husband’s death, in her late 30s, Jamila closed this miserable chapter of her life and moved in with her daughter, my grandmother Amina, in the small town of Narsingdi. At that time, Muslim women were only allowed to stay in either their father’s, husband’s, brother’s, or son’s home. Also, they were allowed to talk only to men who belong in these four categories. Jamila dared to break society’s rules by moving in with her daughter.

She and her son-in-law, Afsar, were the same age. He told me that they became not only close friends, but that she also invested her life savings into his business, which became very successful, eventually becoming a business empire. According to Amina, this was the way her industrialist husband became a highly influential member of society. That meant Amina also got a “promotion,” and more control over their lifestyle. For instance, she gained the freedom for herself and her daughters to choose whether to wear a hijab and a burqa. Because Jamila pushed beyond the difficulties and narrow roles imposed upon her by society, her efforts made it possible not only to develop her abilities and potential, but for her daughter and granddaughter to do so as well.

Jamila, with her character of always swimming in the opposite direction, called my mom “Enragi Ma’am.” This translated to “British lady” in her spoken language. Perhaps by doing so, she sowed a seed in the subconscious minds of the young parents, my grandparents. This seed of hope sprouts. In the next 25 years, it creates a situation where those conservative parents were convinced to allow Razia, my mother, to go to England for her higher studies while she was not married yet — a very unusual case.

Another common trait among us is migration. At some point in our lives, each of us (Jamila, Amina, Razia, and myself) moved to a new location where society presented us with many struggles. Each of us hammered away in anticipation of a better life. Our migration plans were either in or out of Dhaka, a city where we each spent at least 25 years of our lives. The city itself has an interesting history. It was ruled by three different countries during my mom’s lifetime: India until 1947, East Pakistan until 1971, and now Bangladesh.

With my grandma’s full support and her own ambition, my mom became a trailblazer. The first woman in her family to complete high school, she also went past her father and the other men in her family. Eventually, she went to Birmingham University in England, as a Commonwealth Scholar, to pursue her Ph.D. in chemistry.

For my mother, Razia, migration was a temporary thing. She went to England as she understood she would not obtain her desired education in East Pakistan in the 1960s. More than 30 years later, in 1997, I immigrated to the United States to fulfill my dreams. I dreamed to obtain a higher education, a prestigious job, and most importantly, I had the dream to have freedom. I believe that this is the best place in the world to be — where I can have a successful life and continue to have new dreams to fulfill.

The road ahead

Then, even after accomplishing all those dreams, why do I feel that we still have a long way to go? Why do I feel that I am being judged even more intensely here? Back in Asia, I was judged for my gender. Now, why am I judged for my race? My ethnicity? My religion?

The intention of this essay is to express appreciation for the women of earlier generations whose perseverance opened the way for their descendants, while stating my commitment to ensure that any woman can pursue education and a meaningful career in STEM if she tries. I hope that by sharing the successes and failures of each generation who came before me, I can inspire young women, including my 15-year-old daughter, to reach their dreams.

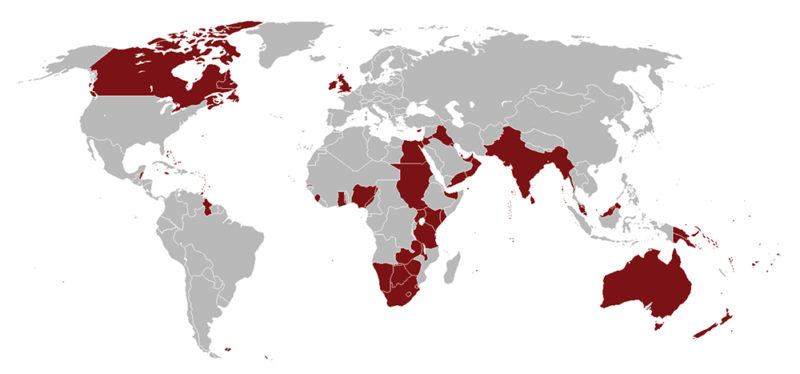

For the SWE family members in this, my adopted country, I have another viewpoint to convey — that the U.S. is now colorful with new citizens, with people like me who immigrated from all over the world. To celebrate this diversity and to make progress together, we must understand, respect, and embrace the backgrounds of one another. Through our hard work, we have achieved some success today. However, we must work harder to pave the road to success for our next generation of women.

Afrin Naz, Ph.D. (she, her, hers), is an associate professor in the computer science and information systems department at West Virginia University and regional co-director of the WVU Center of Excellence in STEM Education. She is chair of the Computers in Education Division of the American Society of Engineering Education. Dr. Naz is also a member of the Society of Women Engineers. She also serves as West Virginia affiliate of the National Center for Women and Information Technology and is an ABET IDEAL Scholar and Google ambassador of West Virginia. She is the founding chair of EMPOWERS, an organization that engages in and creates programs in education, research, and community activities to support and enrich student participation in STEM disciplines in West Virginia, with a primary focus on K-12 female students.